How to Live with Art

Laura Freeman, chief Art Critic of The Times, writes about art collectors in literature, from 'The Pursuit of Love' to 'Burglar Bill,' in a specially commissioned article for Seasons of Story.

There are many reasons to fall in love with Fabrice de Sauveterre, the dashing, aristocratic, homme fatale of Nancy Mitford’s The Pursuit of Love. He is handsome, amusing, rich and a duke. He is an indefatigable talker of gossip and nonsense. He likes to go shopping and adores to pay. Best of all, to my mind, he has taste. He installs our heroine, Linda née Radlett, twice-married to unsatisfactory husbands, in a flat in Paris with south-and-west-facing windows (the best for sunbathing) over the Bois de Boulogne. On the walls are a Gauguin and two Matisses. Linda’s friend Lord Merlin pronounces the Matisses “chintzy, but accomplished.” When Linda needs a Christmas present for Fabrice, she buys him a Renoir seascape for 20,000 francs.

The Gauguin, the Renoir and the two Matisses make a change from the decorative flourishes Linda had grown up with at Alconleigh, the Radlett’s family home, where, over the mantlepiece, in pride of place, hangs the entrenching tool with which Uncle Matthew had whacked eight Germans to death in 1915.

I cannot help but notice what hangs on the walls in a novel. A choice of picture may well tell you more about a character than reams of detailed description. Take Charles Ryder, going up to Oxford in 1922, earnestly decorating his rooms with what he thinks an artistically avant garde undergraduate ought to have around him. A reproduction of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers over the fireplace. A screen, painted by the Bloomsbury artist Roger Fry with a Provençal landscape, which Charles had got cheap when the Omega Workshops sold-up. A poster by Edward McKnight Kauffer whose starkly witty jazz-age designs brightened the corridors of London’s Tube tunnels. No wonder Charles, whose works of art are bargains, prints and posters, is overwhelmed by the Baroque splendour of Brideshead Castle. Charles recalls in a rhapsody:

“It was an aesthetic education to live within those walls, to wander from room to room, from the Soanesque library to the Chinese drawing-room, adazzle with gilt pagodas and nodding mandarins, painted paper and Chippendale fretwork, from the Pompeiian parlour to the great tapestry hall which stood unchanged, as it had been designed two hundred and fifty years before; to sit, hour after hour, in the shade looking out on the terrace.”

Adazzle is the word. To his friend and host Sebastian Flyte it is just the familiar backdrop of home.

Castle Howard, famously used in the 1981 television series of Brideshead Revisited. Adazzle indeed!

How do we live with art? Lock our paintings in climate-controlled vaults? Keep our prints in Solander boxes, sheets of acid-free tissue paper between each page? Cushion our best china in bubble-wrap and take it out only for weddings and funerals?

“Pictures cannot be looked at too much,” was one of the battle-cries of Jim Ede, collector and founder of Kettle’s Yard house-museum in Cambridge. “Look at them and look at them and look at them again.” Visitors to Kettle’s Yard are often surprised to find a Ben Nicholson in the bathroom, an Alfred Wallis above the loo, a sculpture by Constantin Brancusi in the sitting room and a Joan Miró opposite the dining nook. When Jim went away for the week to Paris, he would pack in his attaché case drawings by the sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Christmas cards from the poet and painter David Jones and perhaps one or two of Wallis’s smaller lighthouse or porpoise sea-scenes. However dreary the hotel room, Jim would prop up his pictures and make a gallery and a home from home.

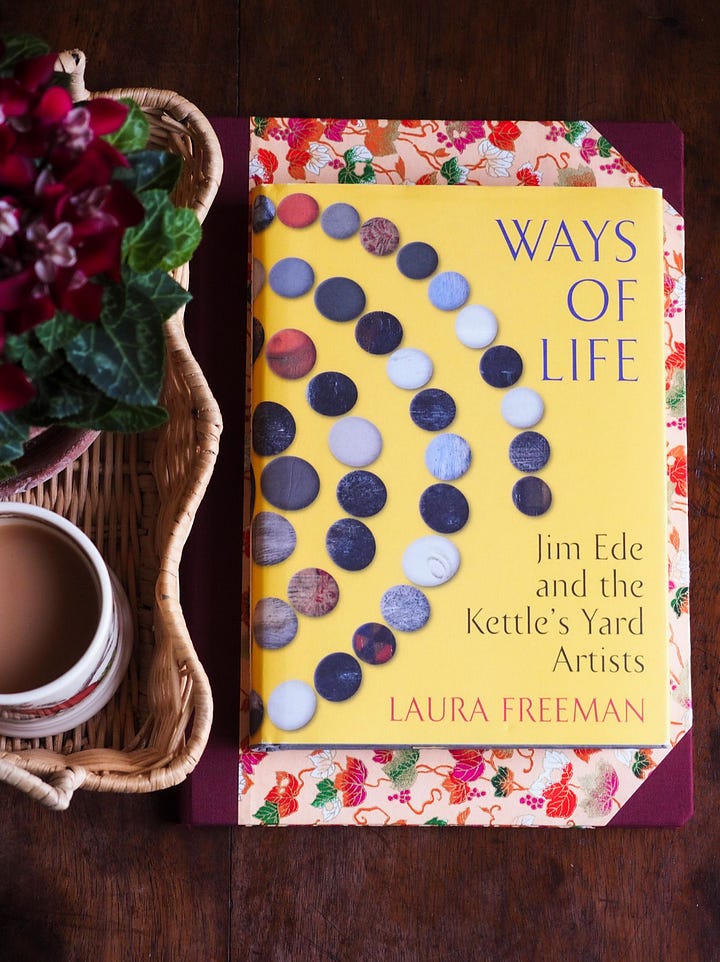

Jim made his collection open to all. On term-time afternoons, he welcomed visitors to the house, gave tours and teas. He lent works of art in the hope that they might brighten student bedsitters. The best collectors share, they do not hoard. While writing Ways of Life, a biography of Jim, I tried to read the authors who had meant most to him. All Jim's long life he had read and re-read Henry James. James’s collectors are rarely generous. They scheme and plot and lust and gloat. What matters is the possession of the object, not the pleasure it might give. Gilbert Osmond in James's The Portrait of a Lady takes a desiccated, obsessive interest in his collection, but there’s no fun or love in the tours he gives around his Florentine villa. He looks covetously at the masterpieces in the Uffizi and the Pitti and his own sister twits him about his “old curtains and crucifixes”. She warns Isabel Archer that Osmond will exhaust her by showing her “all his bibelots and giving you a lecture on each.” Osmond likes to possess his pictures and tapestries and it will suit him to possess Isabel.

There is another hoarder at the cold heart of Edith Wharton’s novella Ethan Frome. The plot turns on the shattering of a prized pickle-dish which the lifeless Zeena stashes in her china-closet: “where I keep the things I set store by, so’s folks shan’t meddle with them.” The dish cannot be reached except by stepladder and the pickle-dish having been put up there on Zeena’s marriage to Ethan has “never been down since, ‘cept for the spring cleaning, and then I always lifted it with my own hands, so’s ‘t it shouldn’t get broke.” Just as you mustn’t put a gun in a story without that gun getting fired, so you mustn’t put a glass dish in a story without it getting broke. When the dish is taken down by the young and guileless Mattie and is shattered in an accident caused by the cat, it sets off a terrible series of events. I hate to see plates and tea-sets locked in cases and kept for best. It’s mean. It’s Zeena.

Reading the Janet and Allan Ahlberg books I had loved as a child to my baby daughter, I realise that she has already met her first collector. The eponymous hero of Burglar Bill clambers through windows and squeezes down chimneys and when he sees something that takes his fancy he says: “I’ll have that.” And he swipes it. Most collectors pay for their spoils, but the Burglar Bill instinct (loot-at-first-sight?) is as true for Guggenheims and Gulbenkians as it is for sticky-fingered fictional burglars. They simply have to have it. I understand the syndrome. When I see an etching at an art fair or spot a mochaware mug in an antiques shop, I am overcome by the greedy feeling of: “I’ll have that.” My mugs, like Jim Ede’s mugs at Kettle’s Yard, are much broken and mended with superglue. Some are so cracked they no longer hold their tea. But I would rather live with art than set it apart on a high shelf. Like Burglar Bill, it is better to say: I’ll have that – to have and to hold, to look at and love.

Laura Freeman is chief art critic of The Times and author of Ways of Life: Jim Ede and the Kettle's Yard Artists. Connect with Laura on Instagram: @laura_freeman_times_art

Photo of Laura Freeman © Alex Winn

Paintings used in this article are: Still Life, Paul Gauguin and View of the Seacoast near Wargemont in Normandy, August Renoir 1880. Article photography © Miranda Mills.

*Note from Miranda: affiliate links are used for Blackwells. If you order a book from Blackwells using one of my affiliate links, I may make a small commission from your purchase, at no additional cost to yourself. I like to support Blackwells by linking to their website, as I’m a big fan of their flagship Oxford bookshop, and they offer reasonable overseas shipping. You in turn support my work by shopping through my affiliate link. Thank you!

Creative Challenge!

Are you a collector? Do you have art in your home, whether paintings on walls or postcards propped up on bookshelves? Perhaps you don't collect art, but you collect something else.

Reflect on your own personal collections. What makes them special to you?

***

Starting in November, our art contributor, Chloë Ashby, will be sharing some of her favourite artworks that reflect each season, building up a virtual art collection for Seasons of Story readers to look at and appreciate.